Monstrous Mothers: Witch Womb is Which?

Mothers in genre fare tend to fall into the same traps, time and again.

This post is free but it’s worth it to become a paid member of The Film Maven community! Paid subscribers are the backbone of The Film Maven who support independent journalism, as well as female- and disabled-created content. Paid Film Mavens get access to two-three exclusive articles a week including access to my series The Trade and Popcorn Disabilities, as well as the ability to chat with me on The Film Maven's Discord server.

Don't want to commit to a subscription? Leave a tip to show you enjoy what you're reading.

Enjoy what you’re reading? Share it with friends. Help us get to 1,000 subscribers by the end of 2025 and I’ll do a full written and video review of Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis.

Read more about the history of disability in film by pre-ordering my upcoming book, Popcorn Disabilities: The Highs and Lows of Disabled Representation in the Movies. I not only expand on what you’re reading here, but examine the stereotypes, tropes, and the good, bad (and really ugly) of disabled movies. Preorder the book by clicking this link! Send me proof of your preorder and I’ll give you a paid subscription to The Film Maven for one year!

According to South Jersey lore, poor Mrs. Leeds, while giving birth to her 13th child cursed the unborn baby and birthed the Jersey Devil: a human-animal hybrid with a tail, wings, and hooves for feet that is said to stalk the Pine Barrens to this day. In that moment, Mrs. Leeds showed her mind’s, as well as her body’s, monstrous reproductive potential. With a single swear spoken in the throes of childbirth, she created a cryptid.

The mysteries of childbirth (including increasingly commercialized gender reveals) have always stirred apprehension, anxiety, and, if something goes wrong, panic. In the event of death or deformity the mother or midwife—those seeming to hold the most power in that moment over life and death—are demonized as a way to shift blame from the father and rationalize loss. As strange as that might sound to us today, a similar, but contemporary example of women blamed for their social and ecological environments is Toxic Town, a British drama series released this year that follows three mothers with children suffering from limb deformity in an area beleaguered by child mortality and health problems due to toxic runoff from steel industries.

Based on a real life court case, the Netflix show follows the area’s economic decline, demonstrating how class and gender figure into our moral judgments on who is most susceptible to unnatural births, and the type of birthing bodies that are perceived as less than human. Within the realm of our contemporary pop culture, including television, reproductive choice is a universal concern that's been shared by creatures of our collective imagination for centuries.

Paula White, televangelist of the “prosperity gospel” and spiritual advisor to President Trump delivered a sermon on January 5, 2020, commanding “all Satanic pregnancies to miscarry right now.” White prayed that anything conceived in Satanic wombs be miscarried, unable to carry forth plans of destruction or harm. A modern day curse cloaked under right-wing rhetoric.

In the aftermath of its eight million views, White tweeted that her remarks referred to a specific Bible passage, “I was praying [Ephesians 6:12] that we wrestle not against flesh and blood. Anything that has been conceived by demonic plans, for it to be canceled and not prevail in your life.” White’s desired divine intercession broadly refers to the end of non-conservation Christian views and Satan’s influence in everyday lives.

One of the most contemporary examples of monsters defined by their motherhood or lack thereof is Yennefer of Vengerberg, from the high-fantasy video game turned series The Witcher (2019). Yennefer shows great magical potential and is recruited to train at an elite school to become a sorceress.

In accordance with the sorceresses' tradition, any physical flaw, including her hunchback, is magically removed. But it comes with a price: her womb. Infertility is a consequence of magic. Yennefer ultimately gets the opportunity to become a surrogate mother through mentoring Ciri, the only remaining heir of the kingdom Cintra. Many individuals streaming the show on Netflix found this particular storyline very cathartic for them as they struggled with their own infertility, and it generated more than a handful of message boards and blog posts of thanks.

Those most affected cited their attachment stemming from feeling a lack of choice in their own fate, and for many individuals who worked and wanted to build a family they saw the magical world of The Witcher delivering a message they’d heard themselves throughout their life: the idea that a woman cannot be in possession of power and also be a mom. You can’t be a witch and be fertile. You can’t be a business owner and have a family.

A Discovery of Witches, a British fantasy television series based on a series by Deborah Harkness, follows New England-born historian Diana Bishop and handsome geneticist and vampire Matthew Clairmont who are drawn to one another despite longstanding taboos about cross-species relationships.

Within the magical world of A Discovery of Witches all three species: demons, vampires, and witches are in decline. So there’s a lot of tension around the future of these creatures individually and in their co-existence. Yet despite the cross-species improbability, Diana, as a weaver and descendant of tenacious pilgrim stock, brings to term two healthy and magical twins. Yennefer’s heritage includes mages and elven blood, and her olive coloring is ethically ambiguous. Diana’s ancestors were pureblooded Puritans— a descendant from a long line of blond hair and blue-eyed Europeans. It's because Diana is who she is, with her distinguishable markers of pedigree and wealth that she is able to exert greater control over their reproductive body.

The presence of black and brown witches and vampires engaged in unfettered family building are still few and far between. In Queen of the Damned Aaliyah has a total of ten minutes of screentime. Even when people of color are billed as the title character they often meet an untimely end, their presence seen as a threat to both a natural and supernatural order. Visual representations of vampires are predominantly distinguished from humans by their porcelain smooth, sparkling pearly white skin. In becoming one of the undead they join a pantheon of creatures with little to none skin pigmentation. Though most never had it to begin with. Pale or white-skinned monsters, especially men and women of leisure such as vampires who canonically sleep through most of their day, indicates just who among the living gets the privilege of eternal life.

Within fiction, there is a growing selection of stories exploring themes of reproduction, desire, and family building by nonnormative, queer, feminist, and POC writers. But by containing these alternative points of view to the page, our media culture can continue to cast birthing bodies– despite having the ability to produce–as monstrous and in need of control. Fledgling, a science fiction vampire novel by Octavia Butler, features a 53-year-old female protagonist who appears to be a ten-year-old African-American girl. It inverts racist notions of blackness as a biological contaminant that leads to degeneracy and instead becomes a necessary trait for the survival of future generations. Criminally, no one’s made a tv show or film of Fledgling, Butler’s final book.

The limitations of making life is a defining characteristic of early vampire narratives intended to curb excessive female sexuality. Most vampiric genesis myths start from an encounter that makes them, a process latent with sexual symbolism: a reclined posture or bent neck, penetration of fangs, and exchange of bodily fluids. Predating Stoker by twenty-six years, in Camilla a young woman is turned away from more “natural desires” by a female vampire.

During the final Season 2 episode of Angel, Darla, Angel’s former lover and vampiric sire, seduces him into having sex with her. Given that they are two consenting adult vampires this shouldn’t be a problem. Except, within the canon of the show, Angel is a vampire with a soul. Should he experience a moment of pure happiness he’ll lose it. Darla goes into this seduction hoping that this will be the precise outcome. However, despite Angel consummating their relationship he doesn’t lose his soul and, plot twist, Darla gets pregnant!

Up until that point no vampires in this universe have ever been known to produce an offspring through a natural pregnancy, so none of their fellow vampires and human companions know what they’ve spawned, though it’s clear that the child is changing Darla. Not only physically, but her monstrous urges grow stronger. To end the ongoing pain, Darla asks Angel to stake her, effectively killing her. Angel refuses; his behavior reminiscent of abortion-debate arguments prioritizing the life of the child over the wellbeing of the mother.

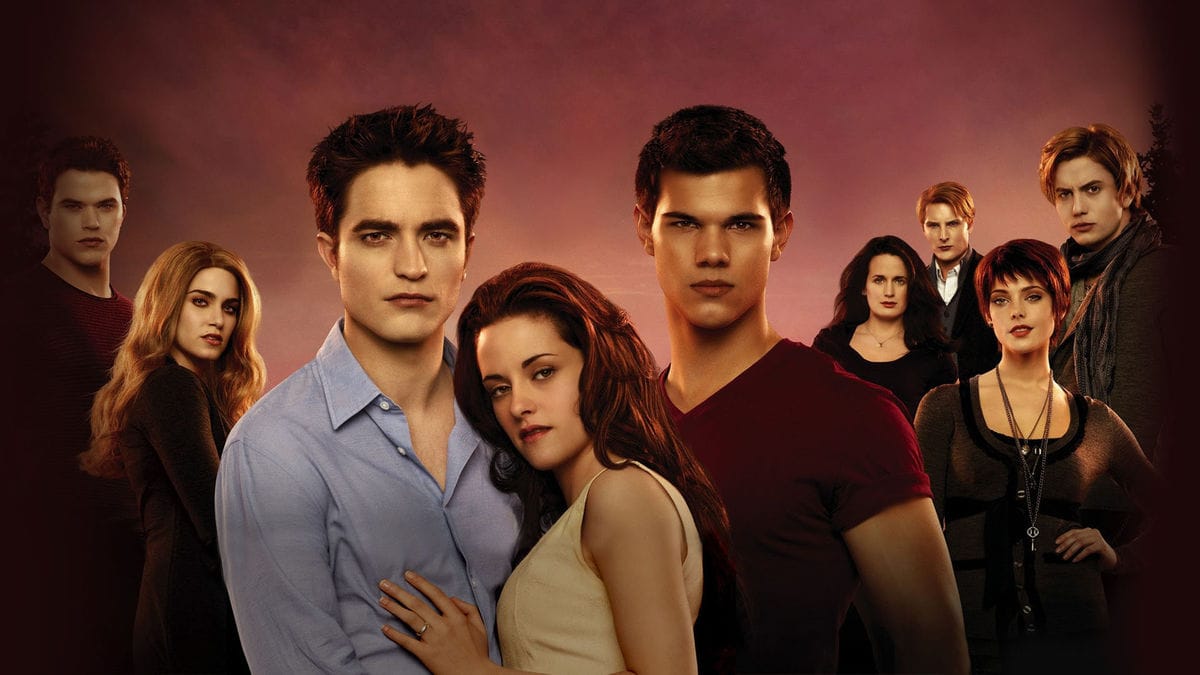

Perhaps the most infamous twenty-first century vampire birth is found in the tween-franchise Twilight by Stephenie Meyer. Twilight is about a young girl named Bella Swan who moves to Forks, Washington to live with her dad and falls in love with the vampire Edward Cullen. Despite the ups and downs of their relationship, and numerous near death experiences, Bella and Edward marry, but their honeymoon is cut short when Bella realizes she’s pregnant.

In Breaking Dawn and Angel, Bella and Darla’s womb originating births render them gestationally grotesque in front of men attempting to rein in what is out of their control and exert power over deviant female bodies. This is not unlike today’s contemporary conservatives.

As Bella’s husband, Edward insists on her aborting the fetus. In contrast to Darla, Bella does not want to rid herself of her baby and feels protective of it, whereas Edward views the child as monstrous and thinks it shouldn’t be allowed to exist. Her pregnancy progresses rapidly, severely weakening her because she is still a human. Edward responds to the news fearfully and confident that his father, a doctor, will get that “thing” out.

Bella nearly dies giving birth to her and Edward's daughter, Renesmee. To save her life, Edward injects Bella with his venom, finally turning her into a vampire, and making Renesmee an only child. Darla, however, is not so fortunate. As she is a vampire at the time of her pregnancy, she ultimately self-sacrifices her monstrous condition for that of a healthy newborn.

The persistent procreation of monsters speaks to, as Ursula Le Guin said, “the incredible realities of our existence.” Gender, as opposed to sexuality, is not exempt from these implicit and explicit conceptions. How many satanic pregnancies are we away from wombs being seen as thoroughly corrupted or corrupting, and therefore requiring even greater governance? The great illusion of the right to choose in each of these movies and myths embodies misconceptions of female anatomy and fear of a white cis-heteronormative male order being broken or questioned because, after all, the writers, creative directors, oral historians, mythmakers and storytellers are only human, each giving new life to our own inherited and increasingly limited reproductive choices.

Some Other Cool Stuff From Kristen:

--I made my L.A. Times debut with this interview with the cast and director of Roofman

The Film Maven is seeking sponsors to help us do more! If you're interested in sponsoring independent journalism get in touch.

Let’s work together! If you have editorial opportunities and would like to collaborate with me on an entertainment or disability project, drop me a message.

Don't want to commit to a subscription? Leave a tip to show you enjoy what you're reading.